Local Binary Patterns (LBP) represent a straightforward, yet remarkably effective, method for analyzing image textures. Numerous online tutorials and resources, including readily available PDF documentation, detail its core principles and practical implementations.

LBP’s popularity stems from its computational efficiency and robustness, making it ideal for various applications, as evidenced by its frequent discussion in online forums and academic papers.

The technique focuses on summarizing the local spatial structure of an image, offering a powerful tool for texture classification and image recognition, as demonstrated in MATLAB code examples found online.

What are Local Binary Patterns?

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) are a class of texture descriptors used in computer vision for image analysis. Essentially, LBP characterizes the texture of an image by summarizing the local spatial structure. This is achieved by thresholding each pixel with its neighboring pixels, creating a binary code that represents the texture information. Numerous PDF documents and online resources detail this process.

The core idea revolves around comparing each pixel to its surrounding neighbors. If a neighbor’s intensity is greater than the central pixel, it’s assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it’s assigned 0. These binary values are then concatenated to form a binary pattern, representing the local texture around that pixel. This pattern is then used to create a histogram, which serves as the texture descriptor.

LBP’s simplicity and efficiency make it a popular choice for various applications, including face recognition, object detection, and image classification. The technique’s ability to capture local texture variations effectively distinguishes it from other texture analysis methods. Online tutorials often showcase practical implementations using languages like MATLAB, further illustrating its accessibility and ease of use; The resulting LBP histogram provides a compact and informative representation of the image’s texture.

Why Use LBP for Texture Analysis?

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) offer several compelling advantages for texture analysis, making them a favored technique in computer vision; A key benefit is its computational simplicity; the algorithm is relatively fast and efficient, even for large images, as detailed in many online PDF guides. This efficiency stems from the straightforward comparison of pixel values and the creation of binary codes.

Furthermore, LBP is remarkably robust to illumination changes. Because it relies on relative comparisons between pixels rather than absolute intensity values, variations in lighting conditions have a minimal impact on the resulting texture descriptor. This robustness is crucial for real-world applications where lighting is often inconsistent.

LBP’s ability to capture local texture information effectively allows it to distinguish between different textures with high accuracy. Numerous tutorials demonstrate its success in tasks like face recognition and object classification. The resulting histograms provide a compact and discriminative representation of texture, making LBP a powerful tool for a wide range of image analysis tasks. Its widespread availability in libraries like MATLAB further enhances its practicality.

Historical Context and Development of LBP

The origins of Local Binary Patterns (LBP) can be traced back to the late 1980s, initially proposed as a texture descriptor for image analysis. Early research focused on its application in texture segmentation and classification, with foundational papers laying the groundwork for its subsequent development. Numerous PDF documents detail this initial phase, highlighting the algorithm’s novelty at the time.

A significant advancement came in the early 2000s with the introduction of Uniform LBP, which reduced the dimensionality of the feature space by considering only uniform patterns. This improvement enhanced computational efficiency and classification accuracy, as documented in several key publications.

Further extensions, such as rotation-invariant LBP, addressed the issue of orientation sensitivity, making the descriptor more robust to variations in image viewpoint. Online tutorials and research papers showcase these advancements. Today, LBP continues to be an active area of research, with ongoing efforts to refine and adapt the technique for emerging applications in computer vision and image processing.

The Core Concept: How LBP Works

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) analyze textures by comparing each pixel to its surrounding neighbors, generating a binary code representing local structure, as detailed in PDF guides.

This process effectively captures texture information.

Defining the Neighborhood

Defining the neighborhood is a foundational step in Local Binary Pattern (LBP) analysis, thoroughly explained in numerous PDF resources and online tutorials. Typically, a grayscale image’s pixel is considered the center, and a circular neighborhood surrounds it. The size of this neighborhood is crucial and is determined by the radius (r) and the number of neighbors (P).

A common configuration utilizes a 3×3 matrix, meaning eight surrounding pixels are compared to the central pixel. However, the radius and neighbor count are adjustable parameters, allowing adaptation to different texture scales and complexities. Larger radii capture coarser textures, while smaller radii focus on finer details. The selection of appropriate parameters is often guided by the specific application and the characteristics of the textures being analyzed.

The neighborhood isn’t limited to a square; a circular neighborhood is more common, ensuring a consistent distance from the center pixel. This circular approach is vital for rotation invariance, a desirable property in many texture analysis tasks, as detailed in advanced LBP documentation available in PDF format.

Thresholding with the Center Pixel

Thresholding with the center pixel is a core operation within the Local Binary Pattern (LBP) methodology, comprehensively detailed in available PDF guides and online resources. This process involves comparing the intensity value of each pixel within the defined neighborhood to the intensity of the central pixel. The central pixel serves as the reference point for this comparison.

For each neighboring pixel, a simple thresholding operation is performed: if the neighbor’s intensity is greater than or equal to the central pixel’s intensity, it’s assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it receives a value of 0. This binary comparison effectively captures the local intensity differences within the neighborhood. This step is fundamental to encoding the texture information into a concise binary representation.

The resulting 1s and 0s represent whether the neighboring pixel is brighter or darker than the center, forming the basis for the LBP code. Numerous PDF tutorials emphasize the importance of accurate grayscale conversion prior to this thresholding step for optimal results.

Binary Code Generation

Binary code generation is the pivotal step following thresholding in the Local Binary Pattern (LBP) process, thoroughly explained in numerous PDF documents and online tutorials. After comparing each neighbor’s intensity to the central pixel and assigning a binary value (0 or 1), these individual binary results are concatenated in a specific order to create the LBP code for that central pixel.

The order of concatenation is typically clockwise, starting from the top-left neighbor and proceeding around the neighborhood. For example, with an 8-neighbor pattern (P=8), the resulting code will be an 8-bit binary number. This binary string uniquely represents the local texture pattern around the central pixel.

Detailed PDF guides often illustrate this process with examples, emphasizing that the generated code captures the spatial relationships of intensity variations. This code is then used to construct histograms, representing the overall texture characteristics of the image, as described in various online resources.

Mathematical Formulation of LBP

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) possess a clear mathematical foundation, detailed in academic PDFs and research papers. The core formula quantifies texture information, enabling precise analysis and comparison, as demonstrated in online resources.

Understanding this formulation is crucial for advanced applications and customization of the LBP technique.

The LBP Formula Explained

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) derive their power from a deceptively simple formula, thoroughly explained in numerous online resources and PDF documents. At its heart, the LBP calculation involves comparing each pixel’s intensity to its surrounding neighbors within a defined radius.

Specifically, for a central pixel Ic, the formula iterates through each neighbor Ip within the neighborhood. A thresholding operation is performed: if Ip ≥ Ic, the corresponding bit in the LBP code is set to 1; otherwise, it’s set to 0. This process generates a binary code representing the local texture pattern.

This binary code is then converted into a decimal value, which serves as the LBP value for that central pixel. The resulting LBP values across the entire image capture the local texture characteristics. Detailed explanations, including step-by-step examples, are readily available in various PDF tutorials and academic publications, clarifying the mathematical underpinnings of this effective texture descriptor.

The formula’s elegance lies in its ability to efficiently encode local texture information into a compact and interpretable format.

Radius (r) and Neighbors (P) Parameters

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) functionality is heavily influenced by two key parameters: the radius (r) and the number of neighbors (P). These parameters, extensively discussed in PDF guides and online tutorials, control the scale and granularity of the texture analysis;

The radius (r) defines the size of the circular neighborhood around each pixel. A larger radius captures coarser texture information, while a smaller radius focuses on finer details. Commonly used values for r are 1 and 2, but the optimal value depends on the specific application and image characteristics.

The number of neighbors (P) determines how many pixels within the radius are compared to the central pixel. Typical values for P include 8 (uniform sampling) and higher values achieved through interpolation. Increasing P provides a more detailed representation of the local texture but also increases computational complexity.

Selecting appropriate values for r and P is crucial for achieving optimal performance, as detailed in various PDF resources dedicated to LBP implementation and parameter tuning.

Uniform Patterns and Their Significance

Local Binary Patterns (LBP) often employ the concept of “uniform patterns” to enhance efficiency and discriminative power, a topic thoroughly covered in available PDF documentation. Uniform patterns are those where the binary code transitions between 0 and 1 no more than twice. This significantly reduces the number of unique LBP values needed to represent a texture.

Instead of considering all 2P possible binary patterns (where P is the number of neighbors), only uniform patterns are retained. This dimensionality reduction simplifies histogram creation and improves computational speed. The remaining non-uniform patterns are often grouped into a single bin.

The significance lies in the observation that many natural textures exhibit predominantly uniform patterns. By focusing on these, LBP becomes more robust to noise and variations in illumination, as explained in numerous online tutorials and research papers.

Utilizing uniform patterns is a key optimization technique for practical LBP applications, detailed in comprehensive PDF guides on texture analysis.

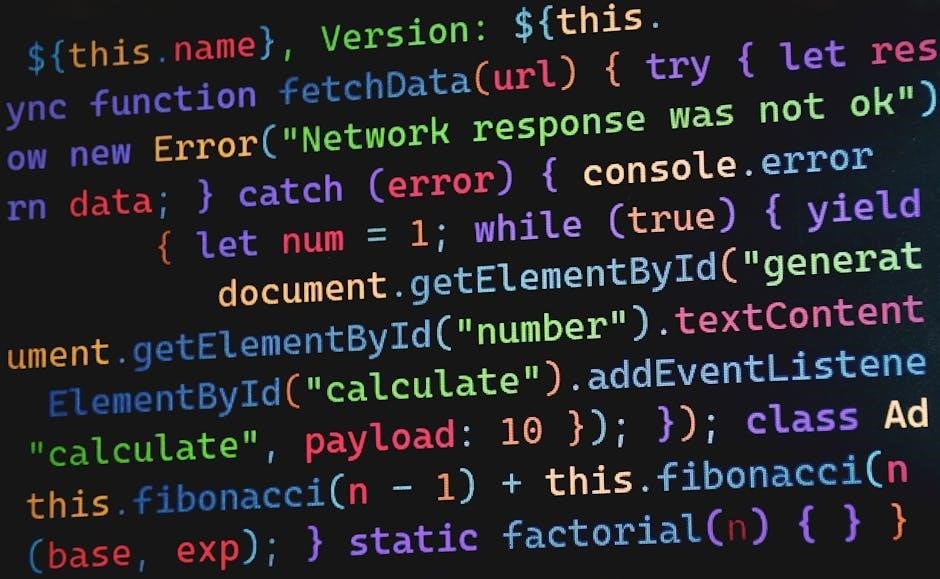

LBP Implementation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Implementing Local Binary Patterns (LBP) involves preprocessing, grayscale conversion, and calculating LBP values for each pixel, as detailed in numerous PDF guides and online resources.

These guides offer practical, step-by-step instructions for texture analysis.

Image Preprocessing for LBP

Image preprocessing is a crucial initial step when implementing Local Binary Patterns (LBP) for texture analysis. As outlined in many PDF tutorials and online resources, the primary goal is to simplify the image data while preserving essential textural information. This often begins with noise reduction techniques, such as Gaussian blurring, to minimize the impact of irrelevant details on subsequent LBP calculations.

A fundamental preprocessing stage involves converting color images to grayscale. LBP operates on intensity values, so color information is typically discarded. This conversion reduces computational complexity and focuses the analysis on luminance variations, which are often more indicative of texture. The quality of the grayscale conversion significantly impacts the final LBP results, and various methods are available, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Further preprocessing steps might include histogram equalization to enhance contrast, particularly in images with poor illumination. This ensures that a wider range of intensity values are represented, improving the discriminative power of the LBP features. Careful consideration of these preprocessing steps is vital for achieving optimal performance with LBP-based texture analysis, as detailed in comprehensive PDF documentation.

Grayscale Conversion

Grayscale conversion is a foundational step in Local Binary Pattern (LBP) implementation, frequently detailed in PDF guides and online tutorials. Since LBP operates on intensity values, transforming color images into grayscale is essential. This process reduces the dimensionality of the data, simplifying calculations and focusing the analysis on luminance variations, which are key indicators of texture.

Several methods exist for grayscale conversion, each impacting the final LBP results. A common approach involves averaging the Red, Green, and Blue (RGB) color channels. However, this method doesn’t account for the human eye’s varying sensitivity to different colors. A more perceptually accurate method utilizes weighted averaging, giving more weight to green, followed by red, and then blue.

The choice of conversion method depends on the specific application and image characteristics. Some PDF resources recommend experimenting with different methods to determine the optimal approach. Proper grayscale conversion ensures that the LBP features accurately represent the underlying texture, maximizing the effectiveness of texture analysis and classification tasks.

Calculating LBP Values for Each Pixel

Calculating LBP values is the core operation within the Local Binary Pattern (LBP) methodology, thoroughly explained in numerous PDF documents and online resources. For each pixel in the grayscale image, a neighborhood – typically a 3×3 matrix – is considered; The central pixel’s intensity value is compared to the intensity of each of its surrounding neighbors.

This comparison involves a simple thresholding operation. If a neighbor’s intensity is greater than or equal to the central pixel’s intensity, a ‘1’ is assigned; otherwise, a ‘0’ is assigned. This process generates a binary code for each pixel, representing the local texture pattern within its neighborhood.

Detailed PDF guides often illustrate this with examples, showing how different intensity arrangements result in unique binary codes. The resulting binary code is then converted into a decimal value, which becomes the LBP value for that pixel. This value encapsulates the local texture information, forming the basis for texture analysis and classification.

LBP Histograms and Texture Representation

LBP Histograms effectively represent texture information, as detailed in many PDF guides. They quantify the frequency of each LBP value across an image, providing a global texture descriptor.

These histograms are crucial for texture classification, enabling differentiation between various surface patterns, and are widely discussed in online resources.

Creating the LBP Histogram

Constructing the LBP histogram is a fundamental step in texture analysis, thoroughly explained in numerous Local Binary Pattern (LBP) PDF resources. This process involves systematically counting the occurrences of each unique LBP code generated across the entire image. Essentially, each bin in the histogram corresponds to a specific LBP value.

Initially, LBP values are calculated for every pixel within the grayscale image, considering its surrounding neighborhood. These values, ranging from 0 to 2P-1 (where P is the number of neighbors), are then used to populate the histogram. For instance, if using an 8-neighbor pattern, the histogram will have 256 bins.

As each LBP value is computed, the corresponding bin in the histogram is incremented. This accumulation provides a statistical representation of the texture, indicating how frequently each local pattern appears. The resulting histogram serves as a compact and informative descriptor of the image’s texture characteristics, readily available for further analysis and classification, as detailed in online tutorials and academic PDF documentation.

Using Histograms for Texture Classification

LBP histograms, detailed in many Local Binary Pattern (LBP) PDF guides, are powerfully utilized for texture classification tasks. Once generated, these histograms become feature vectors representing the image’s textural properties. Comparing these vectors allows for distinguishing between different textures.

Classification typically involves training a machine learning model – such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or a k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) algorithm – using a dataset of LBP histograms from images with known texture labels. The model learns to associate specific histogram patterns with corresponding texture classes.

During classification, a new image’s LBP histogram is extracted and fed into the trained model. The model then predicts the texture class based on the similarity between the new histogram and the patterns it learned during training. Numerous online resources and PDF tutorials demonstrate this process, highlighting the effectiveness of LBP in various texture recognition applications, offering robust and efficient performance.

Normalization of LBP Histograms

LBP histogram normalization, extensively covered in Local Binary Pattern (LBP) PDF documentation, is a crucial preprocessing step for robust texture classification. Variations in illumination or image contrast can significantly affect histogram values, leading to inaccurate results. Normalization mitigates these effects.

Common normalization techniques include dividing each bin in the histogram by the total number of pixels or by the sum of all bin counts. This ensures that the histogram represents the distribution of LBP codes, rather than absolute frequencies. Several PDF guides detail different normalization strategies.

Another approach involves normalizing the histogram to unit length, effectively converting it into a probability distribution. This is particularly useful when comparing histograms from images of different sizes. Online tutorials and PDF resources emphasize that proper normalization significantly improves the performance and reliability of LBP-based texture analysis systems, ensuring consistent results across varying image conditions.

Variations and Extensions of LBP

Numerous Local Binary Pattern (LBP) variations, detailed in available PDF resources, address limitations of the basic method. These include Uniform LBP, rotation-invariant versions, and adjustments to neighborhood sizes.

These extensions enhance robustness and adaptability for diverse image analysis tasks.

Uniform LBP (ULBP)

Uniform Local Binary Patterns (ULBP) represent a significant refinement of the original LBP methodology, addressing the issue of an exponentially growing number of possible binary patterns as the number of neighbors increases. Detailed explanations and implementations are readily available in various Local Binary Pattern (LBP) PDF guides and research papers.

The core idea behind ULBP is to focus only on “uniform” patterns – those that contain a limited number of bitwise transitions (0 to 1 or 1 to 0) within the binary code. This dramatically reduces the dimensionality of the feature space, leading to improved computational efficiency and reduced memory requirements.

For example, with a neighborhood of eight pixels (P=8), a maximum of two transitions is considered uniform. Patterns exceeding this threshold are discarded or mapped to the nearest uniform pattern. This simplification doesn’t significantly compromise descriptive power while substantially enhancing performance. ULBP is particularly effective in scenarios where computational resources are constrained or when dealing with large datasets, as highlighted in numerous online tutorials and academic publications.

The reduction in pattern dimensionality also contributes to better generalization capabilities, making ULBP a preferred choice in many texture classification applications.

Rotation Invariant LBP

Rotation Invariant LBP addresses a key limitation of standard LBP: its sensitivity to image rotations. A texture rotated even slightly will produce different LBP histograms, hindering accurate classification. Comprehensive explanations and code examples for achieving rotation invariance are often found within detailed Local Binary Pattern (LBP) PDF resources and online tutorials.

The most common approach involves generating multiple LBP codes for each pixel by rotating the neighborhood circularly. These rotated codes are then combined, typically by taking the minimum value across all rotations, to create a rotation-invariant feature. This ensures that the feature remains consistent regardless of the image’s orientation.

Alternatively, some implementations utilize Fourier analysis to extract rotation-invariant features from the LBP histogram itself. This method can be computationally more expensive but offers a more robust solution. The choice of method depends on the specific application and the desired trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. Numerous research papers and online guides detail these techniques, providing practical insights and implementation strategies.

Rotation invariance is crucial for applications where the orientation of the texture is unknown or variable.

LBP with Different Neighborhood Sizes

Exploring Local Binary Patterns (LBP) with varying neighborhood sizes is a common practice to capture texture information at different scales. Detailed PDF guides and online resources demonstrate how adjusting the radius (r) and the number of neighbors (P) significantly impacts the resulting texture description. A smaller neighborhood focuses on fine-grained details, while a larger one captures coarser, more global patterns.

Typically, a 3×3 neighborhood (P=8, r=1) is used as a starting point, but experimentation with larger sizes, such as 5×5 or 7×7, can reveal additional texture characteristics. Increasing the radius allows the LBP operator to consider a wider context, potentially improving robustness to noise and variations in illumination.

However, excessively large neighborhoods can blur fine details and reduce the discriminative power of the features. Multi-scale LBP, combining features extracted with different neighborhood sizes, is often employed to achieve a comprehensive texture representation. This approach leverages the strengths of each scale, leading to improved performance in texture classification and analysis, as illustrated in numerous research papers and tutorials.